DKW built its success on its range of small but sturdy budget cars. In 1938, when the threat from Volkswagen to the budget car market was recognized, the company developed the steel-bodied DKW F9 as a budget middle-class car that would occupy a position marginally above the Volkswagen. The Second World War however threw all of these plans into disarray. When the company re-established itself in West Germany after the war, it found it was not able to revive its prewar mainstay budget F8 model, which would have found a ready market in transport starved Germany. Instead, by an improbable series of circumstances, Auto-Union was able to restart personal vehicle production with the F89P New Meisterklasse, which combined the prewar F8 running gear (700cc twin-cylinder engine) with the body of the F9. Although slightly under-powered, the New Meisterklasse definitely fitted into the budget middle-class range, where it competed with the similarly spec'd Volkswagen.

The New Meisterklasse was a strong seller, especially among existing DKW customers who appreciated their high-build quality, ease of maintenance and bulletproof engine. Nevertheless, Auto-Union management recognized that a transport hungry market would be ripe for a very cheap budget car that would appeal to customers who wanted more than a motorcycle but could not yet afford a proper car. Observing the success of other company's microcars, such as the "Messerschmitt", "Zündapp Janus" and "Isetta BMW", in 1952 the company initiated a microcar project that would be run out of the motorcycle department and would be designated "sidecar project."

The motorcycle department took the project brief quite literally and developed a sidecar attachment for the company's range of motorcycles. The problem however, was that the sidecar was too heavy for the motorcycles at that time, which maxed out at only 250ccs. The motorcycle team pressed management to support the develop a new, more powerful range of motorcycles with engines of between 350 and 500ccs. A 350cc model was developed but DKW would never build a 500cc motorcycle in the postwar period.

Karl Jenschke of Ingolstadt's central design office took control of the project. Jenschke reasoned that the type of customer who would consider a microcar would not be off-put by such a vehicles slow speed and low-quality fittings. Jenschke and his team, which included DKW's rising star designer, Kurt Schwenk (designer of the Schnellaster van) drew up a number of conceptual sketches for a three-wheeled bubble car. The concept had no doors, but instead the perplex bubble could be lifted from a pivot at the windscreen to provide access. With modest streamlining and assuming a body of lightweight plastic weighing no more than 250kg, the microcar was envisaged to carry a payload of 225kgs at a speed of 75km/h.

A wood and metal frame mock-up was constructed to test the concept for habitability. A rear-mounted stationary engine of between 200 to 350ccs would provide the power-plant, which gave the project its name - "STM" being the abbreviation of "Stationär Motor."

Models of the concept were shown to the board, who agreed to proceed with a three-wheeled microcar, but then someone suggested that a four-wheeled microcar would be a better investment. The project team agreed to examine both options and this is where things began to go awry. The four-wheel microcar quickly superseded the three-wheeler and then, in its turn, began to grow into a more substantial vehicle than the original microcar concept. The revised four-wheeler would now be powered by a transversely mounted, air-cooled two-cylinder motorcycle engine with a displacement bored out to 400ccm and an output of 15 hp. The drive was via the front wheels. Entry continued to be via a large dome that opened to the rear. The driver sat in the middle, with the two passengers offset to the rear.

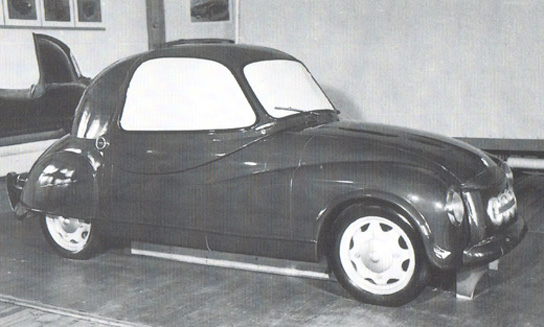

The Auto-Union board did not like the lifting dome access and so the car went back for remodeling as a two-door, which saw the car expand in size and weight further. This model was designated the STM II (see photo below). This is where Auto-Union management revealed itself to be in a state of confusion about the purpose of the STM project. Microcars were expected to be cheap and small, with limited utility. The design committee however could not overlook this and complained that DKW's customers, who were accustomed to the high build quality of DKW's prewar F7 and F8s, would never buy such simple, poorly built vehicle. Talk then began on upgrading the STM to where it could complete with and undercut the Volkswagen, DKW's main rival. This was an impossible task and shortly thereafter Jenschke left the company, taking much of his design team with him.

Kurt Schwenk took over the project from Jenschke and added a new member to his team. Eberan von Eberhorst (below left), was another old Auto-Union hand who had taken over from Ferdinand Porsche has the technical director of the Auto-Union race team in 1937. Eberhorst was responsible for the design of the Auto-Union Type D racers that dominated the Grand Prix circuit immediately before the Second World War. Eberhorst's challenge would be the most difficult one of all - developing a suitably lightweight body for the small car.

The project was reworked from a microcar to a light-weight budget car. The car’s dimensions increased to accommodate 4 passengers in relative comfort. The biggest technical challenge remained manufacturing a suitable body. From the earliest days of the 'sidecar project', the body material had been a matter of fierce debate. Schwenk and Jenschke had both calculated out the maximum weight of the micrcar's body and agreed it must be plastic. The board however had not liked this idea and pressed them to investigate aluminum as an alternative. In post-war Germany there was a lot of scrap aluminum around from the aircraft industry, but it was heavier than plastic and Auto Union had little practical experience with that material.

Before the war, Auto Union was a leading pioneer of Duraplast (resin) panel construction and there were plans to build the body panels of the DKW F9 in Duraplast in 1940-42, however, all of that research was back in Saxony, in the hands of their East German rival, IFA. In a few year's time, IFA would release the first Duraplast-bodied car in the AWZ P70. Nevertheless, Eberhorst managed to pull together a team of chemical and engineering experts and reconstituted Auto Union's Duraplast project. The main problem with Duraplast as a synthetic building material of manufacturing sheets of consistent thickness and structural rigidity. This problem had equally hampered DKW in 1939 and IFA in 1954, but by 1956 Eberhorst’s team had largely resolved the problem. A series of pre-production cars were put together for road trials. The original 'bubble car' (see photo above) was quickly replaced as impractical and the car expanded once again.

All the cars were put though grueling 80,000km tests which demonstrated the Duraplast paneling was viable under all road conditions. All of this effort however would ultimately come to naught. In 1956 and 57, managing director, Dr Richard Bruhn and his successor, Dr Carl Hahn – both stalwarts of the resurrected Auto-Union – retired. Their final years with the company had witnessed executive paralysis and confusion, leaving the company directionless and sliding towards insolvency. Former technical director, William Werner, had been bought back to Auto-Union from the Dutch Berini company in 1956 and stepped into the managing directorship with the promise to take a firm hand on wheel.

From the start, Werner had his eyes set on the STM which had been in the design phase since 1949 and seemed to him no closer to having a production ready car. Werner viewed the cars Duraplast body with disdain, stating German customers would never trust a car body made of plastic - the success of Duraplast-bodied AWZ P70 from East Germany and fibreglass-bodied Chevrolet Corvette from the USA notwithstanding.

It wasn't simply Werner's skepticism of Duraplast as a material. Duraplast DID have a major drawback and one that would ultimately handicap East Germany’s vehicle industry – it required specialized heated panel presses and 15 minutes of curing time to manufacture. In order to build the STM in sufficient volumes to make production economical, Auto-Union would have needed to purchase hundreds of specialized panel presses and substantially change its production operations. Werner and the company’s financiers recognized Auto-Union did not have the capital for this type of expenditure. At the time, Auto Union was seeking State funding to prop up its perilous finances and the government required the company to showcase its new vehicle for evaluation in August 1956. Werner had no confidence in the STM, so he abruptly cancelled the project. Eberhorst resigned, followed by much of the design team.

Auto-Union had lost more than a decade of automobile development with nothing to show for it. The dealer network, which had been shown the STM pre-production cars and assured of a production date in 1957, were outraged to learn that the new car would not be available. With typical energy, Werner designed a completely new car for presentation at the Frankfurt Motor Show in 1957. The resultant DKW 600 was largely based on the STM running gear (chassis, wheels and 600cc twin cylinder engine) but fitted with a steel body with contemporary styling. The DKW 600 actually carried over several styling features of the STM III, such as the fold of rear wing, shape of the windshield, rear window and 12 inch wheels. The display car did not actually run but was a much better-looking vehicle than the STM and the dealer network were placated by Werner’s promises that it would be available the following year. Development of an actual functioning car would actually take two years, by which time the microcar era was over. Auto-Union had missed the boat, but thanks to Werner’s foresight the DKW 600 had been completely upgraded to a budget middle-class vehicle with a newly designed 750cc three-cylinder engine and much improved fittings. The DKW Junior would the last great success for Auto-Union.

The STM test cars were all scrapped, except one of the later version III's, which was used an engine test bed. After Volkswagen purchased Auto Union in 1964, the test car was taken to Ingolstadt to Wolfsburg. After several more years as a test car, it was parked up and forgotten until discovered again in the 1990s. Its condition was still good enough to undertake a restoration.

This is the car that you can see today at the Audi Tradition Museum Mobile in Ingolstadt.

For the aborted FX project - https://dkwautounionproject.blogspot.com/2017/10/the-dkw-fx-would-be-successor.html

For the STM project's part in the decline of DKW - https://dkwautounionproject.blogspot.com/2019/08/auto-unions-small-car-odyssey.html

For the decline of DKW - https://dkwautounionproject.blogspot.com/2019/06/the-decline-of-dkw.html

No comments:

Post a Comment